BSO Office: 9am-5pm M-F

Office Phone: (321) 345-5052

Concert Days: (321) 242-2024

780 S. Apollo Blvd. Suite 218

Melbourne, FL 32901

Mailing Address:

PO Box 361965 Melbourne, FL 32936

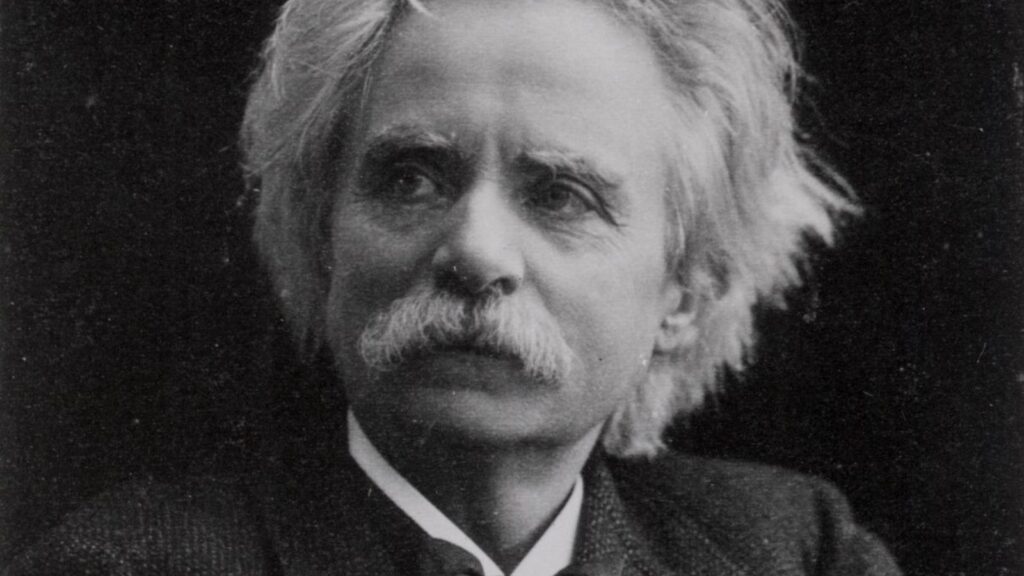

Edvard Grieg was responsible for cultivating a distinctly Norwegian style and presence within the classical world. Born to musical parents in 1843, he began piano at age six, and by the time he was fifteen began studying composition with Niels Gade at the Leipzig Conservatory. In 1880, he returned to his hometown of Bergen to serve as conductor for the Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra. After two years he resigned and dedicated the remainder of his career to composing.

In his mission to create and sustain a uniquely Norwegian aesthetic, Grieg frequently quoted local folk songs or composed new tunes for existing Norwegian dance forms. He combined both elements in his Symphonic Dances, composed between 1896-98, and borrowed melodies from a compilation by Ludvig Lindemann. The dances are in A-B-A form; the A section expands upon the selected quote, and the B section is original material. The first movement is a halling from the Valdres region (just north of halfway between Bergen and Oslo). A halling is a peculiarly acrobatic dance for solo male dancer. Its most distinctive acrobatic feat is the hallingkast, where the dancer flips as he kicks a hat off the end of a stick, positioning a foot above his head. Grieg’s music reflects this character and captures the nature of a dance used for celebratory events like weddings; its ease and continual flow mimic the steady, preparatory spins of the dancer and juxtaposes it with sudden, exuberant bursts of joyous energy.

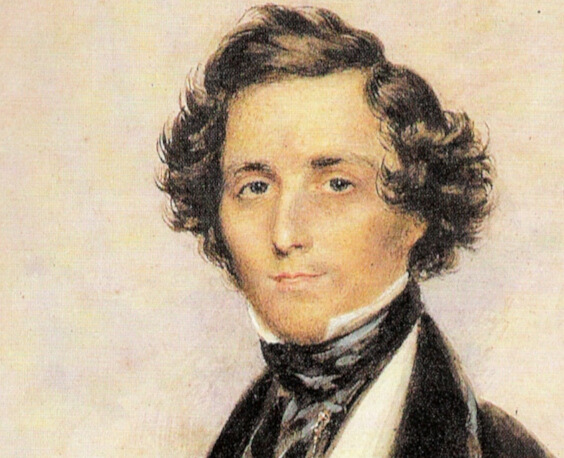

Felix Mendelssohn, a prominent German pianist and composer was appointed to the conducting post of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra in 1835 and immediately invited his friend, virtuoso violinist Ferdinand David, to serve as concertmaster. A letter between the pair, dated 1838, discussed the possibility of a violin concerto for David. As Mendelssohn was in high demand both as a composer and performer, and this was not a deadlined commission, it sat on the side burner for seven years. During this period, he composed the Cello Sonata, “Scottish” Symphony, and the incidental music for A Midsummer Night’s Dream. He also founded the Leipzig Conservatory, Edvard Grieg’s future school. The concerto was completed in September of 1844 and premiered the following March. Although originally intended to be premiered by the two friends with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Mendelssohn’s persistent ill health prevented him from conducting. Niels Gade, Grieg’s future teacher, stepped in for Mendelssohn.

While David provided guidance and feedback for the entire work, David’s hand is most apparent in the first movement’s cadenza and the third movement’s finale. Anecdotally, it was well-known and joked about among David’s colleagues and contemporaries that he could not tolerate playing sustained notes. To the amusement of some and annoyance of others, David was constantly adding trills to long notes. Composer Alfred Richter commented, “The “tingly” liveliness of (David’s) character, as (Richard) Wagner would say, carried over into his playing; as repose did not accord with his nature, he did not like long-held notes.” Knowing this does make the section of continuous trills in the cadenza more amusing! David was also renowned for his exceptional right-hand technique and his bowing versatility is hinted at the cadenza’s end, but the entire third movement is a showcase for the right hand. Long chains of repeated up-bows with minimal down-bows separating them, rapid runs in all registers, and the fiery ending (replete with trills, of course) all accentuate and reflect David’s “tingly” liveliness.

Tying our program together is a friendship that was in part responsible for this concert’s bookends: Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and Edvard Grieg both supported each other and strove for the mutual dissemination of their friend’s music. They dedicated works to each other, programmed each other’s works on their own local concert stages, and shared copies of their compositions. Amusingly, Tchaikovsky once sent a note to Grieg accompanying a new score asking for Grieg’s opinion about a new overture, entitled “1812.”

This friendship and support from Grieg helped to balance the negative, and sometimes harsh, reactions from critics. Fortunately, by the end of his life, Tchaikovsky was enjoying (or not) a bit of public favor and popularity – he was notoriously shy and very uncomfortable receiving adulation, particularly publicly.

Shortly after completing his beloved ballet The Nutcracker, Tchaikovsky began devising a programmatic symphony with an intentionally secret program. His first attempt, however, was scrapped soon after its completion. The result of the second attempt was nothing less than a masterpiece, and Tchaikovsky believed this symphony to be the greatest of his works. In a letter to his nephew, to whom the symphony was to be dedicated, Tchaikovsky discussed his intent to never reveal the secret program to listeners and smugly remarked “Let them guess.”

Tchaikovsky conducted the premiere of his untitled Symphony No. 6 on October 28, 1893, in St. Petersburg and it was both his final composition and live performance. He contracted cholera, which incidentally his mother also died from in his youth and passed away at the tail end of a cholera pandemic. His death, just days after the premiere, came as a shock to both his friends and the public. Conspiracy theories sprang up immediately, with the most extreme asserting that his repressed sexuality developed into a depressive episode that culminated in the taking of his own life. Other rumors went so far as to suggest that he had planned suicide for months and intended the symphony as a requiem. At its second performance, a piece that had been received with polite confusion mere weeks earlier was now heard through the lens of these wild rumors and speculation. Played as a homage concert to the late composer and now bearing the title of Pathétique, it was heard with ears of grief, sympathy, and curiosity. The effects of this mindset, coupled with the burning intrigue over the secret program, have continually captivated listeners.

The full spectrum of human emotion is explored throughout the symphony. The first movement encompasses melancholy, frenetic, and tenderness. The brass solemnly quotes an Orthodox hymn for the dead:

“Give rest, O Christ,

to thy servant with thy saints,

where sorrow and pain are no more;

neither sighing, but life everlasting”.

Despite the 5/4 time signature, the second movement’s off-kilter cello-led waltz is unerringly graceful and lovely. The third movement’s joyous march is led by the clarinet and triumphantly ends with deceptive finality. Thus, the opening notes of the finale are remarkably jarring and emotionally gripping. The finale’s lamenting and descending theme is heart-wrenching and the movement dims to an introspective close.

BSO Office: 9am-5pm M-F

Office Phone: (321) 345-5052

Concert Days: (321) 242-2024

780 S. Apollo Blvd. Suite 218

Melbourne, FL 32901

Mailing Address:

PO Box 361965 Melbourne, FL 32936